He Turned His Three Seven Into Sixes Again Him

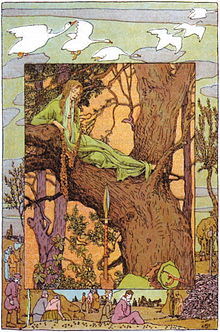

| The Half dozen Swans | |

|---|---|

Analogy by Walter Crane (1882). | |

| Folk tale | |

| Proper name | The Half dozen Swans |

| Data | |

| Aarne–Thompson group | ATU 451 |

| Country | Deutschland |

| Published in | Grimm'south Fairy Tales |

"The Vi Swans" (High german: Die sechs Schwäne) is a German fairy tale collected past the Brothers Grimm in Grimm's Fairy Tales in 1812 (KHM 49).[1] [2]

Information technology is of Aarne–Thompson type 451 ("The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers"), unremarkably found throughout Europe.[3] [four] Other tales of this type include The Seven Ravens, The Twelve Wild Ducks, Udea and her Seven Brothers, The Wild Swans, and The Twelve Brothers.[5] Andrew Lang included a variant of the tale in The Xanthous Fairy Book.[6]

Origin [edit]

The tale was published by the Brothers Grimm in the start edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen in 1812, and substantially rewritten for the 2nd edition in 1819. Their source is Wilhelm Grimm'south friend and future wife Henriette Dorothea (Dortchen) Wild (1795–1867).[2] [7]

Ludwig Emil Grimm Dortchen Wild 1815

Synopsis [edit]

A Male monarch gets lost in a woods, and an old adult female helps him, on the condition that he marry her beautiful daughter. The Male monarch has a bad feeling about this but accepts anyway. He has six sons and a daughter from his get-go marriage, even so, and fears that the children will be targeted by his new wife; so he sends them away and visits them in secret.

The new queen and now stepmother, who has learned witchcraft from her mother, finds out almost her six stepsons and decides to become them out of her way. She sews half-dozen magical shirts and goes to the hidden castle where the children are hidden for condom, then tosses the shirts over the boys and transforms them into swans.

The brothers tin simply have their man forms for 15 minutes every evening. They tell their still human being younger sis that they have heard of a style to intermission such curses: she must make 6 magic shirts that volition allow her brothers turn back to normal out of nettles and tin can't make a audio for half dozen years, because if she does, the spell will never be broken and she will besides transform into swan forever. The girl agrees to do this and runs away, hiding in a hunter'south hut and dedicating herself solely to gathering the nettles and sewing in silence.

Years later, the King of another country finds the girl doing this, is taken by her beauty, and takes her into the court with the intention of making her his queen. However, the Rex'south snobbish mother hates her and does not consider her fit to be a Queen. When she gives birth to their start child, the wicked mother in law takes away the child and accuses the queen of killing and eating him, but the King refuses to believe it.

The young Queen gives birth to ii other children, but twice once more the mother-in-law hides them away and falsely claims that she has killed and eaten her babies. The Male monarch is unable to continue protecting her, and unable to properly defend herself, the queen is sentenced to be burned at the stake equally a witch. All this time, she has held back her tears and her words, sewing and sewing the nettle shirts no thing what.

On the day of her execution, the Queen has finished making all the shirts for her brothers. When she is brought to the stake she takes the shirts with her and when she is near to be burned, the six years expire and the six swans come up flight through the air. She throws the shirts over her brothers and they regain their human form, although in some versions, the youngest brother cannot opposite the transformation completely and his left arm remains a fly due to the missing sleeve in the terminal shirt sewn by his sis.

The queen is now free to speak, and she can defend herself against the accusations. She does so with the support of her brothers. In the finish, the evil mother-in-law is the one who is burned at the stake as penalisation.

Analysis [edit]

Folklorist Stith Thompson points that the stories of the Aarne–Thompson–Uther ATU 451 tale-type follow a long literary history, beginning with the tale of the Dolopathos, in the 12th century.[8] The Dolopathos, in medieval tradition, was later used as part of the Knight of the Swan heroic tale.

Fairy tale scholar Jack Zipes cites that the Brothers Grimm considered an origin in Greco-Roman times, with parallels also found in French and Nordic oral traditions.[nine]

The Brothers Grimm themselves, on their annotations, saw a connection of "The Six Swans" tale with a story of vii swans published in the Feenmärchen (1801) and the swan-ride of the Knight of Swan (Lohengrin). They also saw a connection with the swan shirts of the swan maidens of the Volundarkvida.[10]

On his notes on Children of Lir tale, in his book More Celtic Fairy Tales, folklorist Joseph Jacobs wrote that the "well-known Continental folk-tale" of The 7 Swans (or Ravens) became connected to the medieval cycle of the Knight of the Swan.[11]

Variants [edit]

Distribution [edit]

The tale type is said to be "widely recorded" in Europe and in the Middle East, as well equally in Republic of india and in the Americas.[12] In Europe only, at that place be "over two hundred versions" collected and published "in folktale collections from all parts" of the continent.[thirteen]

French scholar Nicole Belmont identified two forms of the tale type in Europe: i "essentially" present in the Germanic expanse and Scandinavia, and another she dubbed "western version". She noted that in this western version, the youngest sister, subsequently she settles with the brothers, asks for fire from a neighbouring ogre, and a tree sprouts on their yard and bears fruit that causes the transformation.[14]

Variants take also been collected in Japan with the proper noun 七羽の白鳥 (Romanization: Nanaha no hakuchō; English: "The Seven Swans"). Still, Japanese scholarship acknowledges that these tales are restricted to Kikaijima and Okinoerabujima.[xv] Japanese folklorist Keigo Seki also found variants in Kagoshima.[16]

Literary predecessors [edit]

A literary predecessor to the tale is The 7 Doves [17] (Neapolitan: Li sette palommelle; Italian: I sette colombi), in Giambattista Basile'due south Pentamerone, where the brothers are transformed into doves.[18] [19]

Number of brothers [edit]

In the tale from the Brothers Grimm, in that location are 6 brothers and they are transformed into swans.

In other European variants, the number of princes/brothers alternates between three, seven or twelve, but very rarely there are two,[twenty] eight,[21] [22] nine, x or even 11,[23] such as the Danish fairy tale collected by Mathias Winther, De elleve Svaner (English: "The Xi Swans"), first published in 1823,[24] [25] or Ligurian tale Les onze cygnes.[26]

Hungarian folk tale collector Elisabeth Sklarek compiled two Hungarian variants, Dice sieben Wildgänse ("The Seven Wild Geese") and Die zehn Geschwister ("The X Siblings"), and, in her commentaries, noted that both tales were related to the Grimm versions.[27] A third Hungarian is titled A tizenkét fekete várju ("The Twelve Blackness Ravens").[28]

Ludwig Bechstein nerveless 2 German variants, The Seven Crows and The Seven Swans.[29]

Commenting on the Irish gaelic variant collected by Patrick Kennedy, Louis Brueyre indicated equally another variant the Indian tale of Truth'south Triumph,[thirty] or Der Sieg der Wahrheit: in the second part of the tale, the youngest kid, a daughter, witnesses the transformation of her 1 hundred brothers into crows.[31]

In a Lithuanian variant, Von den zwölf Brüdern, die als Raben verwandelt wurden [32] or The Twelve Brothers, Twelve Black Ravens, the witch stepmother asks for her married man to kill his sons, fire their bodies and deliver her the ashes.[33]

In the Hungarian variant A tizenkét koronás hattyu és a csiháninget fonó testvérkéjük, the boys' poor mother curses her twelve sons into the avian form, while also giving an escape clause: after their sis is born, she should sew twelve shirts to save them.[34]

In a Sudanese tale, The ten white doves, the titular white doves are 10 brothers transformed past their stepmother. Their sister has a dream where an old woman tells her the fundamental to reversing the curse: weaving coats with leaves from the acacia tree she is placed on by her brothers after fleeing home.[35]

Results of transformation [edit]

The other variation is in the result of the avian transformation: in some versions they are ducks, in others ravens, and even eagles, geese, peacocks, blackbirds, storks, cranes, jackdaws or rooks.

The hawkeye transformation is attested in the Polish tale[36] Von der zwölf Prinzen, die in Adler verwandelt wurden (English: "The Twelve Princes who became Eagles"),[37] translated as The Eagles.[38] A like transformation is attested in a Romanian tale, which was also compared to the Grimm'due south tale.[39]

The geese transformation is present in the Irish gaelic variant The Twelve Wild Geese, collected by Irish folklorist Patrick Kennedy and compared to the German variants ("The Twelve Brothers" and "The 7 Ravens") and the Norse one ("The Twelve Wild Ducks").[xl]

In a tale attributed to Northern European origin, The Twelve White Peacocks, the twelve princelings are transformed into peacocks due to a curse cast by a troll.[41]

The blackbird transformation is attested in a Cardinal European tale (The Blackbird), nerveless by Theodor Vernaleken: the twelve brothers impale a blackbird and coffin it in the garden, and from its grave springs an apple-tree bearing the fruit the causes the transformation.[42]

The avian transformation of storks is present in a Polish tale collected in Krakow by Oskar Kolberg, O siedmiu braciach bocianach ("The Seven Stork Brothers").[43]

The Hungarian tale A hét daru ("The Seven Cranes") attests the transformation of the brothers into cranes.[44]

The jackdaw transformation is attested in the Hungarian tale, A csóka lányok ("The Jackdaw Girls"), wherein a poor mother wishes her rambunctious twelve daughters would turn into jackdaws and fly away, which was promptly fulfilled;[45] and in the "Due west Prussian" tale Dice sieben Dohlen ("The Seven Jackdaws"), collected by professor Alfred Cammann (de).[46]

The transformation into rooks (a type of bird) is attested in Ukrainian tale "Про сімох братів гайворонів і їх сестру" ("The Vii Rook Brothers and Their Sis"): the mother curses their sons into rooks (as well called "грак" and "грайворон" in Ukrainian). A sister is born years later and seeks her brothers. The tale continues with the motif of the poisoned apple and drinking glass coffin of Snow White (ATU 709) and concludes equally tale type ATU 706, "The Maiden Without Hands".[47]

Folklorists Johannes Bolte and Jiri Polivka, in their commentaries to the Grimm fairy tales, compiled several variants where the brothers are transformed into all sorts of beasts and terrestrial animals, such as deer, wolves, and sheep.[23] [22] [48] Likewise, Georgian professor Elene Gogiashvili stated that in Georgian variants of the tale type the brothers (usually 9) change into deer, while in Armenian variants, they number seven and become rams.[49]

Cultural legacy [edit]

- Daughter of the Forest, the get-go book of the Sevenwaters trilogy by Juliet Marillier, is a detailed retelling of this story in a medieval Celtic setting. A young woman named Sorcha must stitch 6 shirts from a painful nettle plant in order to save her brothers (Liam, Diarmuid, Cormack, Connor, Finbar and Padriac) from the witch Lady Oonagh's enchantment, remaining completely mute until the job is finished. Falling in love with a British lord, Hugh of Harrowfield alias "Ruby", complicates her mission.

- An episode from the anime series Grimm's Fairy Tale Classics,[50] starring Mitsuko Horie as the Princess (here named Elise), Toshiko Fujita as the witch, Hideyuki Hori as the prince, Ishizuka Unsho as the king, and Koichi Yamadera, Taku Takemura, Masami Kikuchi, and Keiichi Naniwa as the brothers. This plot differs in some parts from the Grimm's version, specially in the second part of the story. In the anime, the evil stepmother-queen kills her husband and puts a spell on his children to gain total control of the kingdom similar in the original, merely later she takes up the role of the Princess/Queen's evil mother in law and leaves Elise'due south infant son (her only child) in the forest. The swan-brothers detect their nephew the forest and proceed him live, plus they're stuck in their swan forms all day/night long (though they however tin can speak) until their sister breaks the expletive and they give her the infant back. Elise finishes the garments in time, therefore the youngest is not left with a swan wing in the terminate. When the wicked stepmother is exposed as the witch and every bit the one who framed Elise at the end, she uses her magic in an attempt to escape only then accidentally catches fire from Elise's pyre and burns to death.[51]

- Paul Weiland'due south episode "The Three Ravens" of Jim Henson's television serial The Storyteller is some other retelling of this archetype tale. After the queen dies, an evil witch ensnares the king and turn his three sons into ravens. The princess escapes and must stay silent for iii years, three months, 3 weeks and three days to break the spell. But after she meets a handsome prince, this is suddenly not then piece of cake, for her stepmother has killed her father and remarried - to the prince's father. But when the witch attempts to fire the princess at the stake, the ravens assault her and she accidentally sets fire to herself instead, instantly turning into ashes. Her decease almost fully reverses the spell, but the princess breaks her silence three minutes too soon, and her youngest brother afterward keeps 1 fly forever.[52]

- The novel Birdwing by Rafe Martin follows the youngest prince, homo merely with a fly instead of his left arm, as he grows upward with this "deformity."[53]

- Moonlight features a 13-year-old princess named Aowyn who loses her mother to a mysterious illness, and is charged with protecting her father and her half dozen brothers from the conniving of a witch bent on taking the throne. This retelling is written past Ann Hunter and fix on the Summer Isle, an alternate Republic of ireland.[54]

- The unfinished world by Amber Sparks adapts this story into "La Belle de Nuit, La Belle de Jour", a mixed modernistic-day retelling with fairytale elements such as kingdoms and cars, televisions and golems, and witches and politicians. Hither, the princess is cursed so that her words turn to bees, preventing her from speaking.[55]

- Irish gaelic novelist Padraic Colum used a similar tale in his novel The Rex of Ireland's Son, in the affiliate The Unique Tale: the queen wishes for a blue-eyed, blonde-haired girl, and carelessly wishes her sons to "go with the wild geese". Every bit soon every bit the daughter is born, the princes modify into gray wild geese and wing away from the castle.[56]

See too [edit]

- Knight of the Swan

- Children of Lir

References [edit]

- ^ Kinder und Hausmärchen. Dieterich. 1843.

- ^ a b Ashliman, D. 50. (2020). "The Half-dozen Swans". University of Pittsburgh.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2004). The Types of International Folktales: Creature tales, tales of magic, religious tales, and realistic tales, with an introduction. FF Communications. p. 267 - 268.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. Berkeley Los Angeles London: University of California Printing. 1977. p. 111.

- ^ "Tales Similar To Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs". SurLaLune Fairy Tales. Retrieved 2016-06-05 .

- ^ "THE 6 SWANS from Andrew Lang's Fairy Books". Mythfolklore.net. 2003-07-12. Retrieved 2016-06-05 .

- ^ Meet German wikipedia.de Wild(familie) for more info on tales that came from the Wilds.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. Berkeley Los Angeles London: Academy of California Press. 1977. pp. 110-111.

- ^ The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: the Complete First Edition. [Jacob Grimm, Wilhelm Grimm; translated by] Jack Zipes; [illustrated by Andrea Dezsö]. Princeton University Press. 2014. p. 493. ISBN 978-0-691-16059-seven

- ^ Grimm, Jacob, and Wilhelm Grimm. Kinder Und Hausmärchen: Gesammelt Durch Die Brüder Grimm. 3. aufl. Göttingen: Dieterich, 1856. pp. 84-85.

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph. More than Celtic fairy tales. New York: Putnam. 1895. pp. 221-222.

- ^ Kooi, Jurjen van der. "Het meisje dat haar broers zoekt". In: Van Aladdin tot Zwaan kleef aan. Lexicon van sprookjes: ontstaan, ontwikkeling, variaties. 1ste druk. Ton Dekker & Jurjen van der Kooi & Theo Meder. Kritak: Sunday. 1997. p. 239.

- ^ Angelopoulos, Anna and Kaplanoglou, Marianthi. "Greek Magic Tales: aspects of research in Folklore Studies and Anthropology". In: FF Network. 2013; Vol. 43. p. 11.

- ^ Belmont, Nicole. "Motif «aveugle» et mémoire du conte". In: Bohler, Danielle. Le Temps de la mémoire: le flux, la rupture, l'empreinte. Pessac: Presses Universitaires de Bordeaux, 2006. pp. 185-194. ISBN 9791030005387. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pub.27721. Spider web (en ligne): <http://books.openedition.org/pub/27876>.

- ^ 小高 康正 [Yasumasa Kotaka]. "『グリム童話集』注釈の試み(5)(KHM9~eleven)" [Untersuchungen der Anmerkungen zu den Kinder-und Hausmärchen der Brüder Grimm (5) Nr. 9~11]. In: 長野大学紀要 [Message OF NAGANO UNIVERSITY] Vol. 18, issue 4 (1997-03-26). pp. 73-74. ISSN 0287-5438.

- ^ Seki, Keigo (1966). "Types of Japanese Folktales". Asian Folklore Studies. 25: 117. doi:10.2307/1177478. JSTOR 1177478.

- ^ Basile, Giambattista; Strange, E. F. (Ed.); Taylor, John Edward (translator). Stories from the Pentamerone. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited. 1911. pp. 212-228.

- ^ Canepa, Nancy. Giambattista Basile's The Tale of Tales, or Amusement for Little Ones. Detroit: Wayne Land University Printing, 2007. pp. 350-360. muse.jhu.edu/volume/14344.

- ^ Basile, Giambattista; Croce, Benedetto. Lo cunto de li cunti (Il Pentamerone): Testo conforme alla prima stampa del MDCXXXIV - Half dozen;. Volume Secondo. Bari: Gius, Laterza e Figli. 1925. pp. 207-221.

- ^ "Dice beiden Raben". In: Sommer, Emil. Sagen, Märchen und Gebräuche aus Sachsen und Thüringen 1. Halle 1846. pp. 141-146.

- ^ "Vom Mädchen, das seine Brüder sucht". In: Kuhn, Adalbert. Märkische Sagen und Märchen nebst einem Anhange von Gebräuchen und Aberglauben. Berlin: 1843. pp. 282-289.

- ^ a b Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri. Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm. Erster Band (NR. i-60). Germany, Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 1913. pp. 227-234.

- ^ a b Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri. Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm. Erster Band (NR. 1-60). Frg, Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 1913. pp. 70-75.

- ^ Winther, Matthias. Danske Folkeeventyr, samlede. (Gesammelte dänische Volksmärchen). Kjobehavn: 1823. pp. 7-11. [i]

- ^ Winther, Matthias. Danish Folk Tales. Translated past T. Sands and James Rhea Massengale. Department of Scandinavian Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison. 1989. pp. 5-11.

- ^ Andrews, James Bruyn. Contes ligures, traditions de la Rivière. Paris: Leroux. 1892. pp. 80-82.

- ^ Sklarek, Elisabet. Ungarische Volksmärchen. Einl. A. Schullerus. Leipzig: Dieterich 1901. p. 290.

- ^ László Merényi. Dunamelléki eredeti népmesék (1. kötet). Vol. I. Pest: Kiadja Heckenast Gusztáv. 1863. pp. 115-127.

- ^ Bechstein, Ludwig. As pretty as vii: and other popular German tales. London: John Camden Hotten. [1872] pp. 75-80 and 187-194.

- ^ Frere, Mary Eliza Isabella. Onetime Deccan days; or, Hindoo fairy legends current in Southern India; nerveless from oral tradition. London: Murray. 1898. pp. 38-49.

- ^ Brueyre, Loys. Contes Populaires de la Grande-Bretagne. Paris: Hachette, 1875. p. 158.

- ^ Litauische Märchen und Geschichten. Edited past Carl [Übers.] Cappeller, 146-156. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2019 [1924]. pp. 146-156. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111678931-047

- ^ Zheleznova, Irina. Tales of the Amber Sea. Moscow: Progress Publishers. 1981 [1974]. pp. 187-197.

- ^ Oszkár Mailand. Székelyföldi gyüjtés (Népköltési gyüjtemény 7. kötet). Budapest: Az Athenaeum Részvénytársualt Tulajdona. 1905. pp. 430-435.

- ^ Mitchnik, Helen. Egyptian and Sudanese folk-tales (Oxford myths and legends). Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1978. pp. 85-93.

- ^ "O dwónastu królewiczach zaklętych w orły". In: Gliński, Antoni Józef. Bajarz polski: Baśni, powieści i gawędy ludowe. Tom Iv. Wilno: 1881. pp. 116-127. [ii]

- ^ Glinski, [Antoni Józef], and Amélie (Speyer) Linz. Polnische Volks-märchen: Nach Der Original-sammlung Von Gliński. Leipzig: Yard. Scholtze, 1877. pp. 1-11. [3]

- ^ Polish Fairy Tales. Translated from A. J. Glinski by Maude Ashurst Biggs. New York: John Lane Visitor. 1920. pp. 28-36.

- ^ Gaster, Moses. Rumanian bird and beast stories. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. 1915. pp. 231–236.

- ^ Kennedy, Patrick. The fireside stories of Ireland. Dublin: M'Glashan and Gill: P. Kennedy. 1870. pp. 14-xix and 164.

- ^ A collection of popular tales from the Norse and north German. London, New York [etc.]: Norrna Club. 1906. pp. 162-171.

- ^ Vernaleken, Theodor. In the Land of Marvels: Folk-tales from Republic of austria and Bohemia. S. Sonnenschein & Co. 1889. pp. 29-36.

- ^ Kolberg, Oskar. Lud: Jego zwyczaje, sposób życia, mowa, podania, przysłowia, obrzędy, gusła, zabawy, pieśni, muzyka i tańce. Serya 8. Kraków: w drukarni Dr. Ludwika Gumplowicza. 1875. pp. 38-42. [4]

- ^ János Berze Nagy. Népmesék Heves- és Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok-megyébol (Népköltési gyüjtemény 9. kötet). Budapest: Az Athenaeum Részvény-Társulat Tulajdona. 1907. pp. 223-230.

- ^ Kriza János. Az álomlátó fiú. Budapest: Móra. 1961. Tale nr. 16.

- ^ Cammann, Alfred. Westpreußische Märchen. Berlin: Verlag Walter de Gruyter. 1961. pp. 156-163 and 357.

- ^ "Etnohrafichnyi zbirnyk". Tom 4: ЕТНОҐРАФІЧНІ МАТЕРІАЛИ З УГОРСЬКОЇ РУСИ Tom Ii: КАЗКИ, БАЙКИ, ОПОВІДАНЯ ПРО ІСТОРИЧНІ ОСОБИ, АНЕКДОТИ [Ethnographic material from Hungarian Russia Tome II: Fairy tales, legends, historical tales and anecdotes]. У ЛЬВОВІ (Lvov). 1898. pp. 112-116

- ^ Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri. Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm. Erster Band (NR. 1-lx). Frg, Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 1913. pp. 427-434.

- ^ Gogiashvili, Elene. "THE MOTIF OF THE Faithful SISTER: GEORGIAN AND ARMENIAN VARIATIONS OF INTERNATIONAL FOLKTALE TYPES". In: ՈՍԿԵ ԴԻՎԱՆ – Հեքիաթագիտական հանդես [Voske Divan – Journal of fairy-tale studies]. 6, 2019, pp. 129-130.

- ^ "新グリム名作劇場 第10話 六羽の白鳥 | アニメ | 動画はShowTime (ショウタイム)". 2013-06-22. Archived from the original on June 22, 2013. Retrieved 2016-06-05 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "GFTC - The Six Swans". YouTube. 2014-05-28. Retrieved 2018-01-xi . [ expressionless YouTube link ]

- ^ "The Storyteller Presents The Three Ravens". Angelfire.com . Retrieved 2016-06-05 .

- ^ "Rafe Martin-Birdwing". Rafemartin.com . Retrieved 2016-06-05 .

- ^ Ann Hunter. "Moonlight by Ann Hunter — Reviews, Discussion, Bookclubs, Lists". Goodreads.com . Retrieved 2016-06-05 .

- ^ Amber Sparks. "The unfinished world by Amber Sparks - Reviews, Discussion, Bookclubs, Lists". Goodreads.com . Retrieved 2019-ten-09 .

- ^ Colum, Padraic. The King of Republic of ireland's son. New York: Macmillan. 1916. pp. 130-147.

Further reading [edit]

- Liszka József. "A bátyjait kereső leány (ATU 451) meséjének közép-európai összefüggéseihez" [Notes on the Primal European Correlations of the Folktale Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers (ATU 451)]. In: Fórum Társadalomtudományi Szemle 18. évf. 3. sz. / 2016. pp. 21–34. (In Hungarian)

- Cholnoky Olga. "Liszka József: Egy mesemotívum vándorútja" [The Journey of a Tale Theme]. In: Kisebbségkutatás. 26/2017, nº. 2. pp. 150–153. [overview of the improvidence of the ATU 451 tale-blazon in Central Europe] (In Hungarian)

- Danišová, Nikola. "Morfológia motívu figurálnej transformácie v príbehovej látke o sestre, ktorá hľadá svojich bratov zakliatych na zvieratá" [Morphology of the Motif of Figural Transformation in the Discipline of Stories nigh a Sister Seeking Her Brothers Turned into Animals]. In: Slovenská Literatúra ii, 67/2020, pp. 157-169. (In Slovak).

- de Blécourt, Willem. "Metamorphosing Men and Transmogrified Texts", In: Fabula 52, no. 3-iv (2012): 280-296. https://doi.org/ten.1515/fabula-2011-0023

- Domokos, Mariann. "A bátyjait kereső lány-típus (ATU 451) a 19. századi populáris olvasmányokban és a szóbeliségben" [The emergence of The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers tale type (ATU 451) in 19th-century Hungarian popular readings and orality]. In: ETHNO-LORE: A MAGYAR TUDOMÁNYOS AKADÉMIA NÉPRAJZI KUTATÓINTÉZETÉNEK ÉVKÖNYVE XXXVI (2019): pp. 303–333.

External links [edit]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Six_Swans

0 Response to "He Turned His Three Seven Into Sixes Again Him"

Enviar um comentário